The London Assembly Transport Committee held a public meeting last week on Future Transport, which included a talk on the use of autonomous vehicles in a future London transport network. James Day reports

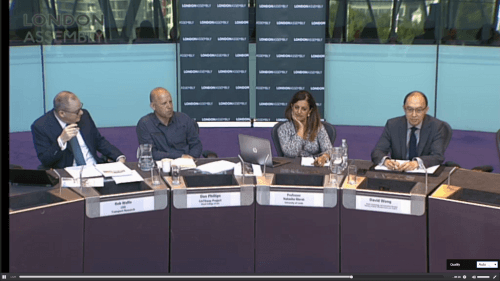

On September 12, 2017, the London Assembly’s Transport Committee was joined by Rob Wallis, CEO of the Transport Research Laboratory (TRL); Dan Phillips from the Royal College of Art, who is the project manager of the Greenwich Gateway project; Professor Natasha Maret, Research Group Leader for Human Factors and Safety at the University of Leeds; and David Wong, Senior Technology and Innovation Manager at the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT).The assembly held a public discussion on autonomous vehicles which was broadcast online. The full broadcast

The assembly held a public discussion on autonomous vehicles which was broadcast online. The full broadcast of approximately three hours, which includes a second public meeting on app-based transport, can be viewed freely at www.london.gov.uk/transport-committee-2017-09-12.

The guests were asked a number of questions on the subject of autonomous vehicles, assessing how soon the technology could arrive, the challenges which needed to be overcome and the impact it would have.[…]

By subscribing you will benefit from:

- Operator & Supplier Profiles

- Face-to-Face Interviews

- Lastest News

- Test Drives and Reviews

- Legal Updates

- Route Focus

- Industry Insider Opinions

- Passenger Perspective

- Vehicle Launches

- and much more!

How soon?

The first questions concerned the likelihood of large numbers of autonomous vehicles on London roads in the next 10-20 years, and what the biggest remaining hurdles are.

Rob Wallis was first to respond: Nobody knows the answer to this yet and it is currently the speculation of organisations and individuals. One of the interesting things for TRL is to look at what the automotive industry is doing and how quickly they are developing products and pushing to bring those products to market.

“Three years from now is the fastest we might get some form of commercial platform available. The real volume adoption of autonomous may take another 10 years or so – around 2030.

“TRL believes this is an absolute revolution, akin to the shift from horse and cart to motor vehicles.”

Dan Phillips responded: “The uptake is going to be dependent on a number of factors, such as technological development, replacement of existing vehicles and political and community support.

“In terms of timescales, we’re already seeing very good autonomous vehicles on the market today, so the market is getting there. From 2020 onwards, I think we will get level three vehicles, and basic autonomous features like advanced cruise control, lane changing, crash avoidance and self-parking will be in most vehicles.

“Between 2025 and 2030, most vehicles will have advanced autonomous control, with some having no steering wheel at all. From 2030 onwards, more and more vehicles will become available without steering, which are more likely to be public or shared vehicles.

“Its moving from using a car to get around, to being in a moving room where you can do other things.

“A good comparison for me is the change from coal fired heating for homes to gas-fired boilers. Coal fired required people, created a lot of pollution and had problems associated with it. With gas, they were all controlled automatically, comfort went up, risk went down, but there are problems with it as well as people might abuse the system.”

Natasha Maret gave a more reserved view: “The technology is technically there now, but there are some barriers before people start using the vehicles. A fully automated vehicle which can go from A to B without any intervention costs around $150k-200k. By 2020, that has to reduce quite massively if that’s going to be privately implemented.

“On the other hand, we have low speed, fully automated vehicles which can go from A to B using maps and radar. These vehicles are already demonstrating, so one could argue they are already available.

“I would say for a fully-automated A to B vehicle, the time is looking like 2030-2040, because of the issues of acceptance, trust, uptake, affordability, infrastructure and so on.”

David Wong spoke last: “Fully autonomous vehicles (where the driver is out of the loop, beginning at autonomous level four) may see some deployment from 2021.

“Then we come to level five vehicles, where there is no steering wheel and there will essentially be no drivers, with the vehicle just carrying passengers and being capable of navigating end to end journeys itself. We are already seeing pods running in geofenced areas within cities. We think 2025 to 2030 we will see the first level five vehicles, but only in very small numbers. Real uptake will likely be 2035 and beyond, depending on a number of circumstances.”

Commercial vehicles

David Wong was first to respond when the topic of commercial vehicles was raised.

He said: “To my understanding, demand responsive buses will be trialled soon in London in a government funded project. That will be an interesting development in terms of deploying commercial vehicles in the form of demand responsive transport.

“This is particularly relevant for last-mile transport in a small geofenced area. We may see deployment of that sort of technology quite soon.”

On trucks, Rob Wallis said: “The go-ahead has been given for platooning trials with trucks. This uses two or three trucks in electronically connected form, where they are able to reduce the distance between each other and close up into a train.

“You get all sorts of benefits – the two drivers behind are able to relax while the platooning is ongoing, but also aerodynamics develop quite a reduction in fuel usage and emissions.

“What’s different in the UK is that we’re trying to test this in real-world environments, rather than a controlled environment. There is now a level of confidence to immerse this in real traffic on public roads.

“The other difference with UK trials is the layout of the motorways. Exit and entryways in the US and Europe, where trials have taken place, are very different, with different distances and so on. Just because it works in France does not necessarily mean it works in the UK.”

Dan Phillips said: “We see autonomous vehicles supporting both people movement and goods movement, and there will be a combination of shared and public vehicles with some private vehicles. They will cover everything from assisting disabled people to providing last-mile inclusive community transport. They will support a solitary person moving around to 20 or more.

“We also think these autonomous systems and the advent of assisted electric motors will provide a bridge between bicycles and larger electric vehicles. We feel there will be a market for electric bikes and electric assisted vehicles which could assist disabled people to get around more easily.

“While we can see people moving away from private cars, some groups, such as families, will still buy them. We’ve also looked at how smaller community buses might deal with last-mile journeys, particularly for older people and people carrying shopping, with intelligent routing to fill in transport deserts.”

Natasha Merat said care must be taken to avoid overloading roads: “While it’s nice to see a large range of possibilities, when there’s still a mixture of technologies what does it mean for a city like London, which is already quite congested?

“What proportion of these vehicles should be public and what proportion should be owned by us? Within the city I would say it would have to be publically owned or public-private partnerships, and for getting to the city you may have privately-owned vehicles which may or may not be autonomous.”

Ethics and safety

With one of the biggest barriers to overcome being safety and ethical concerns, the panel was asked to comment on this topic.

Natasha said: “Level five is the safest level for autonomous vehicles, as by then it has developed into a system which is theoretically foolproof. The manufacturers are suggesting that from level four onwards, they are responsible for the vehicles when they are within the designated autonomous areas.

“In terms of safety, the issues for autonomous levels two, three and four is that the user is not necessarily sure what the vehicle can and cannot do, and terminology can be quite confusing. The most important thing is ensuring drivers are aware of

the vehicle’s capabilities.”

Dan explained: “One of the biggest ethical challenges is the relationship between the computer programme and passengers. It might well be programmed to maximise profit by increasing the number of people picked up and maximising speed, and as such avoid certain areas.

“There’s also the ethical issues around accidents, which I feel are overblown. There’s already evidence that autonomous vehicles crash less. There are all sorts of edge conditions for human beings which don’t happen if you have an autonomous vehicle.

“The insurance for autonomous vehicles is likely to be similar to the airline industry, where there is no blame insurance. You have to see it as systemic, rather than the ‘driver’s’ fault. We also need to prove that the vehicles are capable of driving well. What’s the digital driving test for an autonomous vehicle? Personally, I would love it if a driving test instructor got into an autonomous vehicle and carried out a driving test with the vehicle.”

Rob also stood behind the technology as safe: “Around 95% of deaths and serious injuries on the roads around the world have some element of human interaction which has made a contribution. If you’re able to take the driver out of the equation, there should be a demonstrable reduction in deaths and serious injuries on the road.

“From a regulatory point of view, there are real barriers to overcome. Things like driver licensing – if drivers are not going to drive vehicles, do they need a driving licence? Do they need a different type of driving test for semi-autonomous vehicles? To what extend is someone who is in an autonomous vehicle but over the legal limit for alcohol breaking the law? Can you prove they were in control of the vehicle at a point in time?

“The insurance industry is facing disruption, because drivers may no longer be the insured entity – it may be more the vehicle. There’s also privacy and cyber-security, since the vehicles will have an enormous amount of data on how they have been used and who was using them.

“All of this is just law changes. The biggest challenge we see is the ethical decisions that need to be made, such as when should a vehicle hit a tree and harm the occupants, rather than hit pedestrians and save the lives of the occupants, and other such scenarios. It’s a question that needs to be addressed over the next few years.”

Reducing congestion?

On the congestion subject, Dan commented: “We have to start by making the streets nicer places to be, because if they are not friendly for pedestrians and cyclists then people will choose other ways of getting around.

“Autonomous vehicles should be integrated into the public transport network. If they are not, people will find the benefits they get from their private vehicles are not provided by public transport.

“Next we have to develop a range of different sized autonomous vehicles, so we don’t have everybody using four-seaters when it’s not needed. Smaller two-seaters could be used over larger cabs.

“Sharing needs to be integrated into autonomous vehicles from the start, so vehicles can be shared easily whether publically or privately owned. That will reduce the number of vehicles parked on our streets. We can then consider how to integrate goods movement and people movement into the same vehicles, so you start to have multi-purpose vehicles on the streets.”

Natasha said: “A lot of people use their cars just because of habit. If we encourage people to drop that habit and car share, it will reduce the number of privately-owned vehicles.

“What will make us car share? If it’s comfortable, low cost and saves us time. There are lots of suggestions of how we could increase the use of these publically-owned shared autonomous vehicles. That’s what a city’s of government needs to look into to educate the public and find out what they want. Uber is a good example, where it’s what we wanted as citizens. Unfortunately, according to a DfT report, it has increased privately owned vehicles by 25% in London.

“It shows if autonomous vehicles are not managed and shared, they will increase congestion.”

Rob added: “Research has shown that private vehicles in London spend three quarters of their time on the road looking for somewhere to park. These are journeys, rather than services. If you can start to displace journeys, then even with extra services the traffic on the road may decrease.

“In theory, autonomous vehicles should not need to park – they continue providing services. Clearly they will need maintenance and charging at some point, but it’s a bit like taxis, where you don’t want them sitting on ranks too long, but conducting services on behalf of the general public. We will see an incremental challenge to start with, but a quick shift towards displacement.”

David was also confident that autonomous vehicles would reduce congestion: “A DfT study has said that the modeling undertaken on urban roads with peak traffic and low numbers of autonomous vehicles showed there could be a 12% reduction in delays and a 21% increase in journey time reliability.

“The vision of the automotive industry is ACES – Autonomous Connected Electrified Shared. In terms of shared, we think in the first instance it will be in an urban environment. This would mean high utilisation and occupancy rates and, in theory fewer cars on the road. One shared vehicle can take away five-10 privately-owned vehicles from the road.

“What our members have experienced in terms of running car sharing services is that because of the fragmentation of the boroughs in London and conflicting priorities, they are running into various stumbling blocks. One has exited the market in the UK altogether because they couldn’t make it work.

“When we talk about future transport, what’s also important is distributed digital platforms, to enable people to know where they should go at what sort of time – real-time congestion data. We need to bring all the modes of transport together and empower the consumer to make the decision. We don’t have that all encompassing intelligent mobility system currently.”

Will autonomous combat transport inequality?

On the subject of improving accessibility, Dan said: “If we design the systems right to engage with excluded people, it can improve accessibility by bringing the right vehicle and reducing the cost per mile.

“Autonomous technology has to be inclusive. You have to be able to engage with it, no matter what your physical abilities are.

“There is a big movement in the industry to design more inclusively, but we can go further. Because there may be no need to steer the vehicle, we’ll end up providing better mobility to people currently excluded. We’ve met with a lot of people with mobility issues who are very excited about this independence which they currently lack.”

Natasha stated that the infrastructure must come first: “At the moment these vehicles need nice straight sections of road with white lines to follow. In terms of the transport deserts, they can be served, but the infrastructure and connectivity needs to be in place.”

David said: “We’ve commissioned a study on connected and autonomous vehicles, which revealed that six in 10 foresee a higher quality of life with these vehicles, and half of people with disabilities said that would gain access to new activities they wouldn’t previously be able to reach.

“Two in five believe they would get better access to healthcare, and 47% of older people believe they would more easily fulfill simple day-to-day tasks.”

Rob highlighted positive movements from the industry: “I’m encouraged by the shift from the automotive industry towards services, rather than just manufacturing and selling products. We’re seeing a strong convergence between the two now.

“London needs to make sure the accessibility agenda becomes a key part of the licensing decision and it’s not just the commercial benefits for the organisations coming in and providing those services that are driving the agenda.

It’s important that social inclusion is balanced as part of that.”

Autonomous buses

Briefly towards the end of the panel, the topic of autonomous buses specifically was brought up.

Rob commented: “A lot of work is being done to improve the line-of-sight of bus and truck drivers to allow them to drive more defensively. The introduction of no-driver vehicles can only improve safety over time for vulnerable road users as the technology becomes more robust, but the downside is what that could mean for bus drivers.

“The single most prolific job title throughout the US, for example, included the word ‘driver,’ and a country embarking on automation could potentially find itself with a major economic issue.”

However, Natasha felt that driver jobs are safe for the foreseeable future: “I assume we will see a different kind of automated bus, which will be much smaller and lighter. Full- size buses are more likely to use systems which help to assist the driver to be a better driver for the time being.

“I also think about my colleagues in the aviation industry. After all these years of autopilot, we still have pilots in the cockpit. I’m not sure whether I see all bus drivers suddenly losing their jobs in 20 years’ time. They may just have a different kind of job. Humans will still be needed to watch the systems, even if they get as sophisticated as aeroplanes.

“We have to wait and see how things develop.”