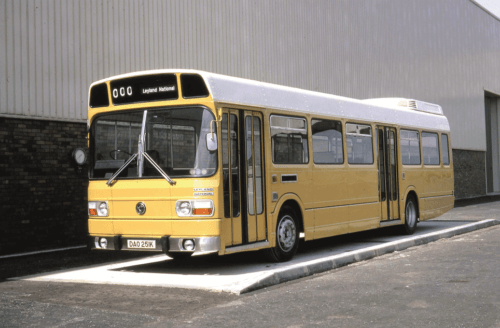

The Leyland National is a bus which has divided opinion since its introduction 50 years ago. Jonathan Welch speaks to former Leyland engineer Basil Hancock about the type’s early life, and looks at some of the unusual variants

Was it a success or a failure? The Leyland National has been the subject of many debates over the years. What isn’t in doubt is that it’s a very ‘Marmite’ bus. With over 7,700 produced, it’s hard to see it as a complete failure; though numbers alone aren’t necessarily a sign of success against a background in which for many operators it was the only choice. Some might say that, for a bus designed to be mass produced, 7,700 is a failure – after all, it was back in 2019 that we reported on the delivery of the 55,555th Mercedes-Benz Citaro, which makes the number of Leyland Nationals delivered in its 14 year production run look like a side-note in the history of single-deckers.

But love them or loathe them, they kept a large part of the country moving for decades, from the introduction of the type in 1972 through to the end of the millennium, with operators such as Chase Bus becoming known for their use of the type.

A brief history

The Leyland National has been written about in books and articles many times in the half century since its launch at the 1970 Commercial Motor Show at London’s Earl’s Court. Work had already been started by Leyland on a new generation of one-man-operated (as it was known at the time) city buses in the 1960s, but it was the company’s merger with the BMC car company and subsequent creation of the Leyland National Company that culminated in the new bus.

[…]

By subscribing you will benefit from:

- Operator & Supplier Profiles

- Face-to-Face Interviews

- Lastest News

- Test Drives and Reviews

- Legal Updates

- Route Focus

- Industry Insider Opinions

- Passenger Perspective

- Vehicle Launches

- and much more!