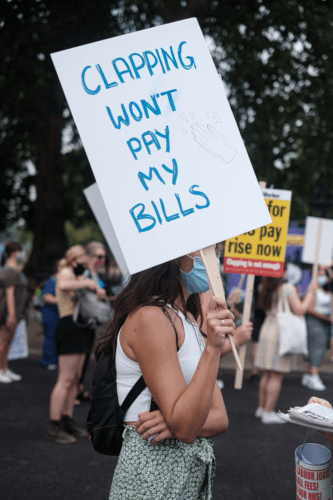

Adam Bernstein discusses the thorny issue of pay rises in the current economic climate

The world is in economic meltdown. Materials and products are in short supply, labour is at a premium – if it can be found – and energy is crucifyingly expensive. And to complete the perfect storm, interest rates are rising – albeit from an all-time low – to combat inflation and as a result of the Government’s recent ‘mini-budget.’

It’s easy, therefore, to see why employees are seeking not just a pay rise, but an inflation-busting pay rise; many are struggling to feed their families, fuel their cars and heat their homes. So what can the sector do to square the circle and keep staff happy while still earning a return on investment?

Pay awards

[…]By subscribing you will benefit from:

- Operator & Supplier Profiles

- Face-to-Face Interviews

- Lastest News

- Test Drives and Reviews

- Legal Updates

- Route Focus

- Industry Insider Opinions

- Passenger Perspective

- Vehicle Launches

- and much more!